Volksdeutschen (ethnic Germans)

The estimated 10-million Volksdeutschen (ethnic Germans) of central- and eastern- Europe were useful prpoganda tools for Nazi Germany. Even before Whermacht troops began their assault on Poland, The German Foreign Office prepared a propoganda offensive. With wildly exagerated accounts of agressions and reports of atrocities against ethnic Polish-Germans by their neighbours. The reconstitution of Poland, following the Treaty of Versailles (1919), made ethnic German minorities of what were ‘Prussian provinces of the German Empire,’ now citizens of the Polish nation state. In September 1939, reports of atrocities against Volksdeutsche accompanied the German invasion of Poland - included were detailed descriptions of rape, dismemberment, and mass slaughter. The “real aggressors,” being, the Poles, Jews, and their allies and backers - presented the Volksdeutschen of Polabd as victims only - and as the only victims.

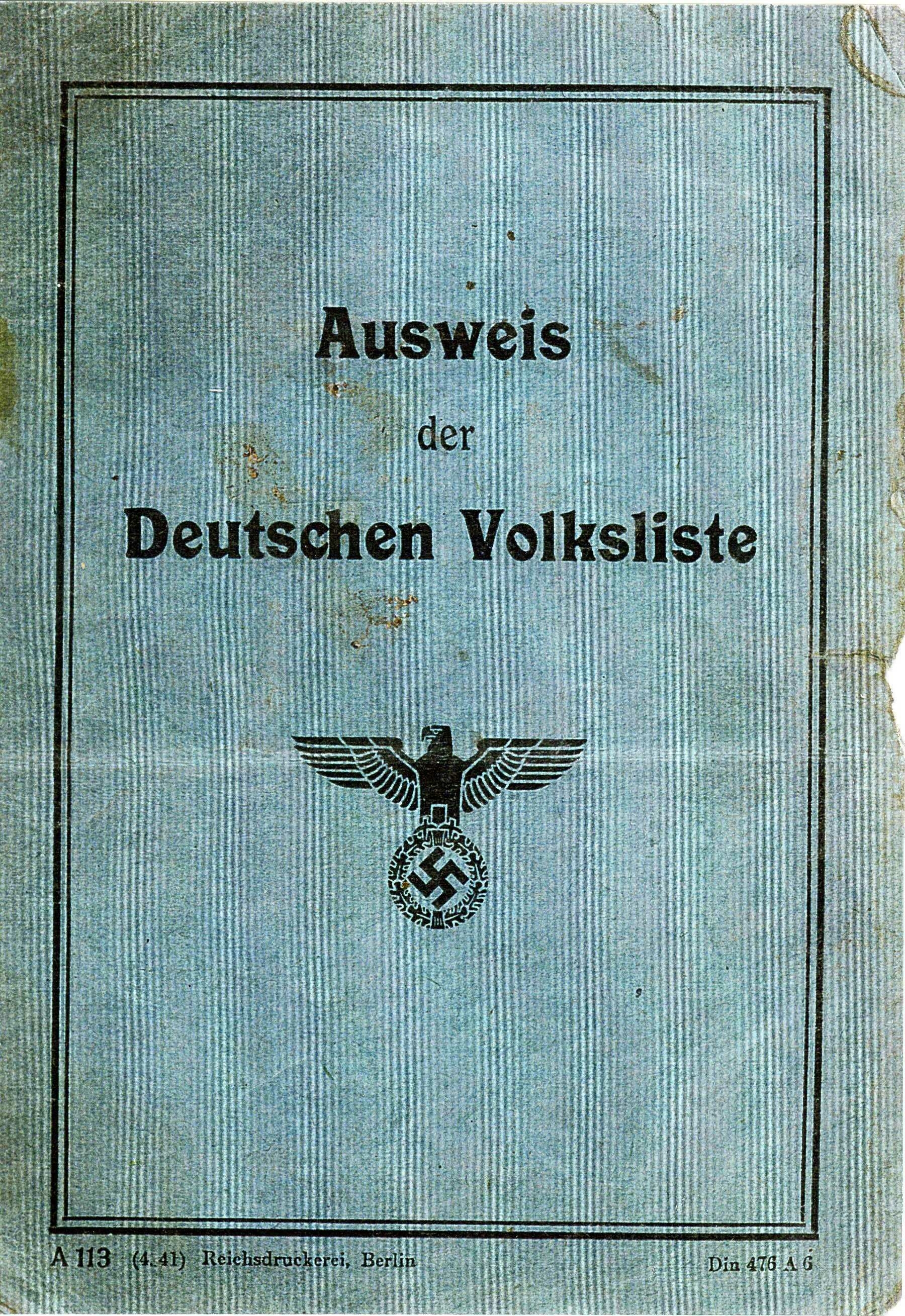

After Germany occupied western Poland, it established a central registration bureau, called the Deutsche Volksliste, DVL (German People’s List)), whereby Poles of German ethnicity were registered as Volksdeutsche. The German occupiers encouraged such registration, in many cases forcing it or subjecting Poles of German ethnicity to terror assaults if they refused. Those who joined this group were given benefits including better food, as well as a better social status.

The Volksdeutsche Mittelstelle [or VoMi, a Nazi Party agency founded, in 1937, to manage the interests of the Volksdeutsche and responsible the implementation of Nazi Lebensraum, “living-space” policies, see blog post,] organised large-scale looting of property and redistributed goods to the Volksdeutsche. They were given apartments, workshops, farms, furniture, and clothing confiscated from Jews and Poles. In turn, hundreds of thousands of the Volksdeutsche joined the German forces, either willingly or under compulsion.

During WW2, the Polish citizens of German ancestry that identified with the Polish nation faced the dilemma whether to register in the Deutsche Volksliste. Many families had lived in Poland for centuries and more-recent immigrants had arrived over 30 years before the war. They faced the choice of registering and being regarded as traitors by the Poles, or not signing and being treated by the Nazi occupation as traitors to the Germanic race.

Polish Silesian Catholic Church authorities, led by bishop Stanisław Adamski and with agreement from the Polish Government in Exile, advised Poles to sign up to the Volksliste in order to avoid atrocities and mass murder that happened in other parts of the country.

In occupied Poland, Volksdeutscher enjoyed privileges but were subject to conscription, or draft, into the Whermacht. In occupied Pomerania, the Gauleiter of the Danzig-West Prussia region Albert Forster ordered a list of people considered of German ethnicity to be made in 1941. Due to insignificant voluntary registrations by February 1942, Forster made signing the Volksliste mandatory and empowered local authorities to use force and threats to implement the decree. Consequently, the number of signatories rose to almost a million, or about 55% of the 1944 population.

Ethnic German colonisers, resettled into German-annexed and occupied Poland during “Heim ins Reich” action (see my blog post]. The Deutsche Volksliste categorised non-Jewish Poles of German ethnicity into one of four categories: Category I: Persons of German descent committed to the Reich before 1939. Category II: Persons of German descent who had remained passive. Category III: Persons of German descent who had become partly “Polonised”, e.g., through marrying a Polish partner or through working relationships (especially Silesians and Kashubians). Category IV: Persons of German ancestry who had become “Polonised” but were supportive of “Germanisation”.

Volksliste of Category 1 and 2 in the Polish areas annexed by Germany numbered 1-million, and Nos. 3 and 4 numbered 1.7-million. In the General Gouvernement there were another 120,000 Volksdeutsche.